Greenland, the GIUK Gap, and Arctic Security

See The Simons Foundation Canada's Arctic Security Briefing Papers for information on military policies and practices in the Arctic region by Ernie Regehr O.C., Senior Fellow in Arctic Security and Defence at The Simons Foundation Canada.

Greenland, the GIUK Gap, and Arctic Security

Greenland’s strategic significance has long been linked to the “GIUK gap” and, more recently, to the Island’s reportedly abundant and widely coveted natural resources. Presidential musings about an American takeover to satisfy the Administration’s perceived security requirements are now part of the discourse, and, inevitably, the requisite strategic rationales have been proffered to support those security claims – though not generally the takeover ambitions. Meanwhile, it remains for the rest of the Arctic to reaffirm Greenland/Denmark sovereignty as they evolve it, and to ensure that what ultimately endures is the collective regional commitment to cooperation.

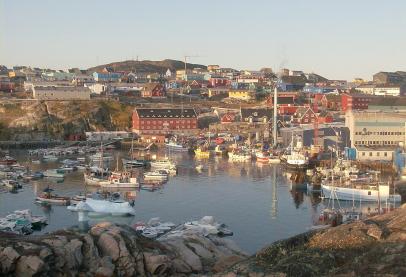

Going on two decades ago, the Arctic’s coastal states gathered in Greenland’s Ilulissat to declare that the Arctic thrives when cross border cooperation, based on mutual trust and the rule of law, is validated by commensurate action. Now the US president’s commentaries on Greenland[i] and the implied actions not only flout that commitment, they also ignore the sovereignty of a NATO partner by insisting that America must own or control Greenland to assure American, and even world, prosperity and security.

So far, President Donald Trump’s musings have not referred to a long-standing focus of Pentagon and NATO interest, namely the GIUK gap. This is the maritime chokepoint between Greenland, Iceland, and the United Kingdom, which all Russian sea traffic heading south from Kola Peninsula bases must traverse to reach the North Atlantic and beyond. Thus, for decades the North Atlantic has been a prominent NATO and American arena of surface and especially sub-surface surveillance.

The Canadian Armed Forces, by the way, have been regular participants in those operations. An August 2023 report on deployments in the seas east of Greenland, issued through the North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (NAADSN), referred to the 2018 NATO Trident Juncture exercise in which Canada’s contribution was the fourth largest.[ii] Greenland marks the western end of the GIUK gap and hosts the American space base in the north at Pituffik. Iceland’s place at roughly the mid-point of the gap, welcomes NATO air forces at its Keflavik airport. The United Kingdom marks the eastern end of the GIUK gap.

Hyping Greenland’s security significance

It is the Trump rhetoric, not any new realities on the ground or in the water, that seeks to elevate Greenland to “linchpin” status in a geostrategic “framework” that stretches “from the South China Sea, over the Arctic, to the Black Sea.”[iii] Before Trump started talking about buying Greenland or otherwise making it American territory, few if any mainstream strategic analysts were casting the strategic importance of Greenland in such extravagant terms, much less insisting America should own it.[iv]

But now, the President’s persistent, if vague, insistence on Greenland’s extraordinary security significance for the United States has set the stage for at least some sympathetic pundits and strategists to make the case for its key strategic importance.[v]

One of the most enthusiastic iterations of analysis hyping Greenland’s strategic value comes from a Republican strategist writing in NewsMax. He credits Trump with being “the first world leader to recognize the tactical advantage to be gained” by acquiring Greenland and, among other things, by establishing a submarine base there, the better “to track Russian submarine movements in the Arctic and North Atlantic.” Ultimately, the analysis concludes that “acquiring Greenland is not just an option – it is imperative.”[vi]

Others also promote the centrality of Greenland to American or Western security, although for most that doesn’t lead to a need for the US to “own” it. Still, they do describe the island’s security importance in elevated terms. At Strategy International, Greenland is said to be “a pivotal point in the competition for military, economic, and energy dominance situated in the heart of emerging maritime passages between Europe, Russia, and North America.” It also, however, warns that rhetoric about American control “could ultimately backfire and jeopardize US interests,” like “undermining the West’s unity, rules-based order, and the principle of sovereignty.”[vii]

War on the Rocks argues that “American national security depends on defeating Arctic-based threats to North America while blocking Russian and Chinese power projection into the North Atlantic and North Pacific.” It goes on to conclude that “Greenland is the geostrategic linchpin connecting the Arctic, North America, and Europe — a potential the United States and Denmark have yet to fully leverage.”[viii]

While the President now covets Greenland, The War Zone describes more modest ambitions, pointing out that

“there are several places there where the U.S. and NATO allies can increase their anti-submarine capabilities without taking over the entire island. That begs the question of why expend the enormous diplomatic and potentially financial capital to acquire it? Iceland also has a regular detachment of anti-submarine warfare aircraft from the U.S. that covers the GIUK gap, making access for these operations in Greenland seem like more of a convenience than a necessity.”[ix]

The Pentagon’s 2024 Defense Arctic Strategy[x]shows no signs of coveting Greenland. As one might expect, its “foremost objective is to protect the security of the American people, including those that call the Arctic home,” and focuses more on the Arctic as “an avenue for [American] power projection to Europe and is vital to the defense of Atlantic sea lines of communication between North America and Europe.” Its reference to the GIUK gap simply notes it as an area for “continuing airborne and maritime patrols with Allies across the Arctic region to include areas such as the Greenland-Iceland United Kingdom gap.” There is no reference to the critical, or unique, importance of Greenland to American security.

An analyst at Washington’s Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), notes Greenland’s strategic value, including a location that is “critical to monitoring the so-called Greenland–Iceland–United Kingdom gap…for Russia’s Northern Fleet.” But he argues that Trump’s pursuit of a takeover, and his threats to the use of force to that end, amount to “taking a sledgehammer to the last remnants of Arctic exceptionalism—the notion that the Arctic is governed by unwritten rules, beliefs, and history that have protected it from great-power rivalry.”[xi]

Focusing on the gap

The context that continues to drive attention to the GIUK gap remains the threat of a NATO/Russia war in Europe. Analysts have long warned that the most likely scenario for armed hostilities in the Arctic is spillover from Russia-NATO hostilities in Europe. The focus of such scenarios is Russia’s formidable military capacity based on the Kola peninsula, which in a crisis would head toward the European theatre of combat and, notably, the North Atlantic to aid the Russian war effort.[xii] NATO would seek to prevent Russia’s considerable Arctic war-making capabilities from reaching the theater of war, especially by trying to impede Russia’s Kola-based Northern Fleet in its movements south to the North Atlantic and beyond, where it would challenge NATO transportation and communications links with North America, as well as potentially strike European and North American targets with sea-based weapons.

In the latter case, the US has become particularly concerned about possible sea-launched Russian conventional attacks on the American homeland, notably using newly developed hypersonic cruise and glide weapons, not only to interrupt movement of materiel and reinforcements to Europe, but also and perhaps especially to threaten North America directly, and thus to undermine the increasingly fragile political will to sustain US participation in European security and ultimately war.[xiii] A new reality for the US is that it can no longer count quite as confidently on its armed forces facilities (domestic and overseas) being “safe havens” from adversary attack.[xiv] It has become conventional wisdom that Russia is keen to push its submarines “to get as far out into the Atlantic as possible without being discovered,” and thus to demonstrate that it “is able to threaten the US East Coast,”[xv] and even further inland. The fear is that “the development, acquisition, and deployment of stealthy air and sea-launched cruise missiles, and the modernization of the aircraft and submarines that deliver them [to which can be added aspirations about hypersonic missiles], has given Russian military planners their first true conventional capability to strike the Continental United States.”[xvi]

A key objective of NORAD modernization therefor is to develop effective defences against conventional attacks which are not considered to be amenable to nuclear deterrence. One element of that effort is NATO’s ambition to fortify defences in the GIUK gap.

Russia would of course seek the reverse – to prevent NATO from blocking the Northern Fleet’s advance southward, and to “flood into the GIUK Gap and the waters off Norway in a defensive posture to keep U.S. submarines and surface combatants from pushing northward during a crisis.”[xvii]

Russia has little incentive to spread a European conflict into the Arctic. Its interests are to prevent attacks on its Arctic region and to keep its northern economic resources and military forces at the ready to reinforce and sustain its more southerly war efforts. That is why it focuses so heavily on defensive upgrades in places like Franz Josef Land (the Nagurskoye base) to extend Russia’s anti-access/area denial objectives over the Barents Sea and into the Norwegian Sea toward the North Atlantic.

Changing perspectives on the strategic climate

Greenland has been affected by shifts in the strategic climate for a long time – notably during World War II and the earliest post-war years, then the dawn of the Cold War and NATO, through periods of East-West détente and heightened tensions. Throughout, the GIUK gap has been in the West’s sights. But never has there been a serious ambition to make Greenland American – Greenland is, after all, already a thoroughly entrenched part of NATO. Greenland’s positioning and role have throughout been accepted on the basis of it being a sovereign, and cooperative, entity within Denmark, and any actions now contemplated in the GIUK gap can be done by and in cooperation with its three sovereign entities – threats, by foe or friend, to Greenland’s sovereignty have no political, legal, or security justification. Continue reading...

Ernie Regehr, O.C. is Senior Fellow in Arctic Security and Defence at The Simons Foundation Canada; Research Fellow at the The Kindred Credit Union Centre for Peace Advancement, Conrad Grebel University College, University of Waterloo; and co-founder and former Executive Director of Project Ploughshares.

[i] For example:

“We need Greenland for national security and even international security, and we’re working with everybody involved to try and get it. But we need it, really, for international world security. And I think we’re going to get it. One way or the other, we’re going to get it.” Remarks by President Trump in Joint Address to Congress, The White House, 06 March 2025. https://www.whitehouse.gov/remarks/2025/03/remarks-by-president-trump-in-joint-address-to-congress/

In response to reporters in Oval office: "We need Greenland for national security and international security,...So we'll, I think, we'll go as far as we have to go. We need Greenland. And the world needs us to have Greenland, including Denmark. Denmark has to have us have Greenland. And, you know, we'll see what happens. But if we don't have Greenland, we can't have great international security. I view it from a security standpoint, we have to be there." David Brennan, “Trump says US will 'go as far as we have to' to get control of Greenland,” ABC News, 27 March 2025. https://abcnews.go.com/International/trump-us-control-greenland/story?id=120208823

[ii] “This included two frigates (HMCS Halifax and Ville de Québec) and two Maritime Coastal Defence Vessels (HMCS Summerside and Glace Bay), 1000 personnel from 5 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group consisting of a light infantry Battalion (3rd Battalion, the Royal 22nd Regiment) and a Brigade Headquarters, eight fighter aircraft (CF-188 Hornets), two maritime patrol aircraft (CP-140 Auroras) and one airborne refueling aircraft (a CC-150 Multi-Role Tanker Transport Polaris). With 2,000 troops forward deployed, it has been by far the biggest, most complex military operation for the Canadian Forces since Afghanistan. It was supported by roughly 170 sea containers and 80 vehicles brought over by ship, many flights by CC-177 Globemaster III cargo aircraft and 10 chartered commercial flights to move personnel. At a cost of $28 million, Canada had sent the fourth largest national contingent to Norway.”

Ryan Dean, “Military Threats In, To, and Through the Arctic East of Greenland and Implications for Canada,” The North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network (NAADSN), August 2023. https://www.naadsn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/East-of-Greenland-report-RD.pdf

[iii] Aaron Brady, “Greenland’s Military Possibilities for the United States,” War on the Rocks, 04 April 2025. https://warontherocks.com/2025/04/greenlands-military-possibilities-for-the-united-states/

[iv] Brett Tingley and Tyler Rogoway, “The U.S. Can’t Buy Greenland But Thule Air Base Is Set To Become More Vital Than Ever Before,” The War Zone, 01 December 2019. https://www.twz.com/29541/the-u-s-cant-buy-greenland-but-thule-air-base-is-set-to-become-more-vital-than-ever-before

[v] A quick and decidedly unscientific Google search of the military strategy site, The War Zone, yielded 44 articles on the site referring to Greenland between November 8, 2016 and April 3, 2025. Without doing an exhaustive review of the content of each article, and relying largely on the titles of each, the only articles (both quoted in this briefing) addressing the unique strategic place of Greenland appeared in early 2025 after President Trump’s musings on taking it over as an American territory because it is essential to American security. Neither advocated an American takeover of Greenland, but both highlighted its strategic significance. All the others addressed Greenland only in the context of discussing topics like the operations of the American base there, the GIUK gap, NATO, and Danish exercises. One 2019 Article refers to Trump’s early speculations about “buying” Greenland, but it focused on an extensive account of the then Thule Air Base and its growing importance to the US – the American base’s “lasting strategic importance,” and noting that, “as the Arctic heats up both literally and geopolitically, Thule could become a cornerstone of America’s military strategy in what is a looming military competition in the northernmost corner of the world” (Tingley and Rogoway, 2019).

A similar search of the War on the Rocks site found 50 Articles referencing Greenland from August 2014 to the present. Again, most referred to Greenland largely in passing – in the context of the GIUK Gap, more extensive references with a focus on China and resources, Russian patrols in Greenland’s northern seas, the American base, North Warning system radars, and indigenous lands. In 2019 there were a couple of references to Trump’s musings about buying Greenland but not supporting it. In 2025 a couple of articles argue against the US trying to take over Greenland, and Aaron Brady’s article, quoted above, offers an extensive argument for the strategic importance of Greenland, calling it, as already noted, a lynchpin.

[vi] Rob Burgess, “Greenland: A National Security Imperative for the US,” NewsMax, 14 April 2025. https://www.newsmax.com

[vii] Ioanna Salinka, “Greenland holds great importance for the United States,” Strategy International, 24 February 2025. https://strategyinternational.org/2025/02/24/publication163/

[viii] Aaron Brady, 04 April 2025.

[ix] Howard Altman, “Greenland ‘Absolutely Critical’ For Hunting Russian Submarines: Top US General In Europe,” The War Zone 03 April 2025. https://www.twz.com/sea/greenland-absolutely-critical-for-hunting-russian-submarines-top-u-s-general-in-europe

[x] “2024 Arctic Strategy,” UN Department of Defense, 21 June 2024. https://media.defense.gov/2024/Jul/22/2003507411/-1/-1/0/DOD-ARCTIC-STRATEGY-2024.PDF

[xi] Otto Svendsen, “Seizing Greenland Is Worse Than a Bad Deal,” Center for International and Strategic Studies, 21 January 2025. https://www.csis.org/analysis/seizing-greenland-worse-bad-deal

[xii] Ernie Regehr, “Combat ‘Spillover’ – into and out of the Arctic,” The Simons Foundation Briefing, 10 March 2021. https://www.thesimonsfoundation.ca/sites/default/files/Combat%20%27Spillover%27%E2%80%93into%20and%20out%20of%20the%20Arctic%20%20Arctic%20Security%20Briefing%20Paper%2C%20March%2010%202021_0.pdf

[xiii] Heather A. Conley and Matthew Melino, “America’s Arctic Moment: Great Power Competition in the Arctic to 2050,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 2020. https://csiswebsiteprod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fspublic/publication/Conley_ArcticMoment_layout_WEB%20FINAL.pdf?EkVudAlPZnRPLwEdAIPO.GlpyEnNzlNx

[xiv] Howard Altman, 03 April 2025.

[xv] Howard Altman, 03 April 2025.

[xvi] Terrence J. O’Shaughnessy and Peter M. Fesler, “Hardening the Shield: A Credible Deterrent & Capable Defense for North America,” The Canada Institute of the Wilson Center, September 2020. www.wilsoncenter.org/canada

[xvii] Howard Altman, 03 April 2025.